Robin Hood's Well (Nottingham)

| Locality | |

|---|---|

| Coordinate | 52.9713, -1.1242 |

| Adm. div. | Nottinghamshire |

| Vicinity | NE Nottingham, St Ann |

| Type | Monument |

| Interest | Robin Hood name |

| Status | Defunct |

| First Record | 1500 |

| A.k.a. | St Ann's Well; Saynt Anne Well; The Brodewell; Owswell |

By Henrik Thiil Nielsen, 2016-10-15. Revised by Henrik Thiil Nielsen, 2021-02-12.

Robin Hood's Well a.k.a. St Ann's Well was located in the north-eastern neighbourhood of Nottingham now known as St Ann, an area that was once part of Sherwood Forest and retained a bucolic character until the mid-19th century.[1] The well, known by several names, played an important role in Nottingham civic life over the centuries. From the late 1550s on, borough records list expenses relating to a procession of the mayor and members of the civic administration, wearing their official liveries and accompanied by musicians, to the well for a festive dinner in or outside the adjacent woodward's house.

The history of the well from the mid-16th century to its destruction in the late 19th century is intertwined with that of the woodward's house, so both are treated together here.

Names of the well

The well is perhaps referred to in Nottingham civic records for 1301 as 'The Brodewell', but this is uncertain as this name was also applied to another well.[2]Robin Hood's Well was apparently also known as Owswell during the Middle Ages.[1] From an early date its water was believed to be endowed with curative and restorative powers, and like so many other springs in the medieval period it became a holy well. In 1409 a chapel dedicated to St Ann was built next to it,[1] and by 1577 the well had come to be known as "Sent Anne Well".[3] However, already in 1500 the well was referred to as Robin Hood's Well and in 1578 as 'Robyn Hood Well alias Saynt Anne Well'. The latter is the name under which the well is mentioned in Nottingham civic records from the 17th century on and may thus be regarded as the official name. Yet, according to Nottinghamshire historian Charles Deering, the name 'Robin Hood's Well' could still be heard in the mid-18th century (see Records and 1751 allusion cited below).[4]

Early history of the well

Joe Earp writes in his very readable and informative blog article on St Ann's Well that "[t]he term Well rather than Spring was used to imply that the ʻspring headʼ had been covered or artificially channelled in the remote past".[5] Many native English speakers, I think, now tend to make this distinction between 'spring' and 'well', but applying it to a place-name of medieval origin would be anachronistic. The primary meaning of the noun 'well', recorded since early Old English times, is "[a] spring of water rising to the surface of the earth and forming a small pool or flowing in a stream".[6] The place-name element 'well' therefore does not tell us whether the spring was covered or not.

In 1216, according to Earp, Nottingham was granted for the use of its poorer inhabitants the meat of deer culled during spring, and the distribution of this developed into an Easter feast at the well, an occasion that was still celebrated in post-Reformation times. From c. 1100 to 1312 the site was 'run' as a holy-well by the Templar 'Brotherhood of Lazarus'. Eventually control of the well was taken over by the monks of Lenton Priory, who dedicated the well to St Ann and, in 1409, built a chapel dedicated to that saint next to it. For all this Earp cites only secondary sources, one of which is quite untrustworthy.[7] I hope further research will reveal if his account can be corroborated by primary sources.

Civic outings 1557–1623

Arguing against the civic procession to the well originating in an early 13th century venison dole-out is the fact that civic records and documents, which survive from the mid-12th century on,[8] do not mention the procession until 1557/58, when a payment to "Maister Byron's Keypers at Seynt Anne Well on Blacke Mondey" (i.e. Easter Monday) is recorded.[9] We may also note that a mid-16th century local writer states explicitly that the custom was begun and kept up in order to support financially the town's woodward who was keeper of the "victualling house" where the festive dinner took place (see anonymous source cited in 1751 Quotation below).

Three entries of payments to named musicians or anonymous town waits for performing en route to the well and at the well are recorded, the latest in 1575/76.[10] Records for 4 Nov. 1577 include the request "that here myghe [i.e. may] be a cover made at Sent Anne Well, as you and youre bretheryn may devise as consernyng, eyther att the Chappell end or at summ place convenyent where you shall thynke good off".[11] This, which probably indicates that there was no well cover before this time, cetainly is proof of continued official interest in keeping up the well. Yet a couple of decades later it is clear that some members of Nottingham's civic elite, whether out of parsimony, penury or some other motive, were less than enthusiastic about the procession-cum-dinner. For civic records for April 1601 include this entry:

Goinge to Saint Ane Well. — Itt ys ordened that the Aldermen, the Councell, and the Cloathinge shall wayte on Maister Maior on Blake Monday yearely to Saint Ane Well, there to spend theyr money with the Keper and Woodward: upon payne of euerye Alderman makinge defalt and not pardoned by the Maior to forfeyt ijs., of the Cloathinge to forfeyt xijd., beinge not pardoned by the Maior. And that euerie of the Aldermen shall spend there with the townes Woodward ijs., and with the Thorney Wodes Keeper att discretion; euerye Counceller, with the townes Wodward xviijd', and with the Keeper in discretion; euerye of the cloathinge to spend with the townes Wodward xijd., and with the Keeper at discretion. And that none of them shall carry or send any provision thither.[12]

On 10 April 1609 it was decided "that the meeting att Saint Ane Well shall hould" and that "the Cownsell and Cloathinge" must "bee there, and [...] sytt togeather according to theyr seniorities, and [...] pay xvjd. a man all alyke"[13] The woodward's house at which the dinners took place was rebuilt 1617/18 to 1619, when the records include entries of expenses on materials and labour. In 1619 a kitchen was built or perhaps rather an existing one rebuilt[14] Also in the latter year expenses were recorded "for wine and suger at the Well on Blake Mundaye".[15] According to the 1751 allusion cited below, the woodward's house, a brick building, was built on the spot where the Chapel of St Ann once stood, one wall of the house being made of stone was "the East Wall of that quondam Chappel [which] supports the East side of the House". He continues: "In the Room of the Altar is now a great Fire-place, over which was found upon a Stone the Date of the building of the Chappel, viz. 1409".

On 23 March 1620/21, "[t]he companie are agreed thatt the former order touchinge the accompaniinge Maister Maior to Saint Anne Well shall stand, and either to goe or pay, or bothe." The latter means, as the editor of the records explains in a note, "that members of the Council are to be fined unless they attend."[16] On 15 April 1622 it was "agred, thatt the antient meetinge att Saint Anne Well shall stand; and this companie haue promised to goe thither on Black Monday nexte, or ells to send theere monies, in regard the poore man makes provisions for them." On 28 March 1623: "Thee metinge on Blacke Monday to hold accordinge to the antient custome, butt with this addicion, thatt Maister Maior, Aldermen and Shreves pay ijs. a peice, and all the Clothinge and Councell present xviijd., and all absent xijd."[17] After this there are no more entries relating to the procession or dinner.[18]

Royal and bourgeois conviviality 1624–1751

It was decided on 21 July 1624 in expectation of James I's visiting the well that "Maister Robert Parker, Maister John James, Maister Alvey, Maister Hopkyn are required to deale with Edward Allsebroke, Maister Kyme, Gabriel Dun, and Maister Callton for theire closes nere the Well to be preserved against the Kinges cominge, and to take order for the fencinge thereof"[19] We do not know whether His Majesty King James I found the surroundings sufficiently tidy, though an anonymous mid-17th century writer was an eye-witness to the "Royal and remarkable Assembly at this Place" when "it pleased our late Sovereign king James, in his Return from Hunting in this Forest, to Honour this Well with his Royal Presence, ushered by that Noble Lord Gilbert Earl of Shrewsbury, and attended by many others of the Nobility, both of the Court and Country, where they drank the Woodward and his Barrels dry" (cited in the 1751 allusion below). Unless this brief account refers to an earlier royal visit that has left no mark on the local records – and this seems unlikely – its author must be mistaken with regard to the Christian name of the Earl of Shrewsbury. Gilbert, 9th Earl of Shrewsbury, died in 1616. The Earl present at the royal visit to the well in 1624 must have been John Talbot, 10th Earl of Shrewsbury (1601-1654).[20]

It may be no more than a coincidence that the royal visit occurred the year after the very last mention of the civic procession to the well. However, a royal visit obviously increased the prestige of the venue – if only for a time and at this date not necessarily in the eyes of all potential customers – and it is conceivable that increased custom made the civic procession-cum-dinner unnecessary. It is clear from the records relating to the event cited above that the annual dinner was an indirect means of civic sponsorship of the woodward's establishment at the well. According to the 1751 allusion cited below, this official was an employee of the mayor's. Perhaps it was decided that the keeper could now do without the city's official sponsorship. The rising tide of Puritanism and individualism swept away many communal customs, perhaps this was one of them.

In all events the nine volumes of published civic records[21] contain no further reference to the dinner at the well after 1623. Yet judging by the 1751 allusion cited below and the anonymous account, about a hundred years older, which is in turn cited in it, it seems clear that business at the woodward's must have been brisk when the weather was fair and on holidays. According to the anonymous mid-17th century writer, the "Victualling House" by the well in addition to the woodward's private habitation included "a Building containing two fair Rooms, an upper and a lower" to which visitors resorted when the weather was inclement. Outside were "fair Summer-Houses, Bowers or Arbours covered by the plashing and interweaving of Oak-Boughs for Shade, in which are Tables of large Oak Planks, and are seated about with Banks of Earth, [...] and covered with green Sods, like green Carsie Cushions." Here visitors would enjoy meals, drink, talk and music in fair weather, the season lasting from March to October. It was a pleasant c. 2 km walk from town to the well. "Thither do the Townsmen resort [...] by an ancient Custom beyond Memory". As is hinted at in one of the records relating to the civic procession cited above, it was possible to bring one's own food or have it sent to be prepared at the woodward's. Townsfolk "use [...] to fetch a walk to this Well, either to dine or sup, or both, some sending their provision to be dressed, others bespeaking what they will have, and when any of the Town have their Friends come to them, they have given them no welcome, unless they entertain them at this Well." Attractions included "Artificial" as well as "Natural Music without Charge; in the Spring by the Nightingale and in the Autumn by the Wood-Lark".

About a hundred years later the situation seems to have been much the same. Visitors could be "entertained with a Concert of Areal Musicians in Nottingham Coppices, or on Mondays and Wednesdays join in Company with those who use the Exercise of Bowling." The well, considered the second coldest in all England, was "frequented by many Persons as a cold Bath". Charles Deering described the well and its surroundings in 1751, noting that to the north of Nottingham, but separated from it by large fields:

[...] are two large Coppices appertaining to Nottingham, and thence called Nottingham Coppices, which formerly were well stored with Oaks and Underwood, one of these, viz. the upper Coppice is cleared and turned into Pasture Land, the lower Coppice is still tolerably well provided with Underwood, neither is it altogether destitute of Timber.

ON the North side of the Town are two Springs, one arises almost at the Foot of the last mentioned Coppice, it is walled in and covered with a Tiled Roof, the waste of it runs in a small Channel through the midst of the Fields [...] The other springs forth about half-way between the Town and the former, it is not quite so large, is also walled about and an Iron dish used to hang by a Chain for Passengers to drink at, the Waste of this, first runs into a Stone Trough, and thence in a small Trench proceeds and falls into the Channel of the former, thus forming one Current they make their way by the side of the Town and cast themselves into the Leen. These springs are of the same use to the Cattle on the North, as the Rivers are on the South side, the other parts of the Fields which are somewhat remote from both, are mostly provided with Wells.[22]

Robin Hood's Well aka St Ann's Well is the first of the two wells described by Deering.

Robin Hood paraphernalia for the great unwashed

An additional attraction at the woodward's was by 1751 (see Allusions section below) a quaint little collection of ostensible Robin Hood paraphernalia:

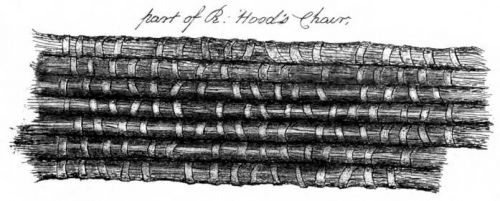

The People who keep the Green and Public House to promote a Holy-day Trade, shew an old wickered Chair, which they call Robin Hood's Chair, a Bow, and an old Cap, both these they affirm to have been this famous Robber's Property; [...] this little Artifice takes so well with the People in low-Life, that at Christmas, Easter and Whitsuntide, it procures them a great deal of Business, for at those Times great Numbers of young Men bring their Sweethearts to this Well, and give them a Treat, and the Girls think themselves ill-used, if they have not been saluted by their Lovers in Robin Hood's Chair.

It is hardly possible to say how long these objects had been on display at the establishment, but wicker chairs are not the most durable of artifacts, By 1790 only a fragment of R. Hood's Chair was left, while as one would expect, the iron helmet seems to have been in rather better shape (see illustrations). I am not aware that any depiction of the bow exists. According to Bob White, the collection of Robin Hood paraphernalia also included his arrows, boots and bottle.[23] Mr White cites no source for this. In 1827 the collection of Robin Hood paraphernalia was sold at auction to a Lionel Raynor, "a famous actor on the London stage", and "introduced into a melo-drama at one of the London theatres" (see 1840 allusion below). Raynor is said to have offered these items to the British Museum before migrating to the United States. However, the British Museum holds no record of such an offer.[24] If the Robin Hood relics were in fact used for a London show it may be possible to trace their fate further through contemporary newspaper and magazine articles, reviews etc.

Decline at the well

When James Orange visited the well in 1839, "the sylvan bowers [,] the umbrageous glens, and all the gay delights and laughing pleasures of woodland scenery" (see 1840 allusion below) were gone. The former coppice was now arable land. The changed scenery may well have made the fomer woodward's house a less attractive venue for a holiday outing. Perhaps there is also in Deering's account a hint of a change in the demographic composition of the clientele. The young louts "saluting" their girlfriends from Robin Hood's chair sound more like drinkers than diners. At any rate, in 1825 the establishment lost its licence to serve alcohol "[i]n consequence of sabbath breaking, fights and tumults so often happening" (see 1840 allusion below). This must have hit economy hard, for as we have seen, the collection of Robin Hood paraphernalia, though very likely still a drawing card, was auctioned a couple of years later.

In 1840, James Orange noted that "there is a delightful garden and pleasure ground, in which the company are allowed to walk, and there are swings for young people to amuse themselves; but the rarest object of attraction is the ingeniously formed maze cut out in the green sward." Here youngsters who take on the challenge of the Shepherd's Race must "run, or they would fall or tread upon the grassy side, which is to lose the race, and the constant turning and winding about of the path-way awakens the utmost vigilance in the breast of the earnest aspirant of youthful fame." Orange felt, not without some hyperbole, that "[n]o sight is more pretty or engaging than to behold six or eight young girls and boys running at the same moment the varying and seemingly interminable windings of the Shepherd's Race."

All these attractions notwithstanding, after catering to diners and drinkers for centuries the old woodward's 'victualling-house' was out of business a few decades after its licence was withdrawn. Fun without alcohol just isn't the same.[25]

The Age of Steam fills in the well

St. Ann's or Robin Hood's Well was filled up and the site covered by an embankment when a suburban railway was constructed in August of 1887.[26]

Records

1500 - Disturbance near Robin Hood's Well (Nottingham)

[20 July 1500:]

3Et dicunt, quod Robertus Wyly, de Sneynton, in Comitatu Notingham', husbondman'. aggregatis ei diversis aliis ignotis ad numerum sexdecim personarum modo guerrino arraiatis, vicesimo quarto die Aprilis, anno regni Regis [Henrici quinto] decimo,4 vi et armis, videlicet, baculis et cultellis, vangis et tribulis ac aliis armis defencivis, solum commune Majoris et Burgensium villae Notingham' in tenura Johannis S[elyok] apud Notingham praedictam, juxta Robynhode Well'. injuste fregit, effodit et subvertit, in grave detrementum dictorum Majoris et Burgensium villae praedictae ac dicti Johannis Selyok, et contra pacem dicti Domini Regis, etc. 9 d., ro. 3.

[Translation in printed source:]

3And they say that Robert Wyly, of Sneinton, in the County of Nottingham, husbandman, having gathered to himself divers other unknown men to the number of sixteen persons arrayed in warlike manner, on the twenty-fourth day of April, in the fifteenth year of the reign of King Henry,4 with force and arms, to wit, with clubs and knives, spades and shovels and other defensive arms, unjustly broke, dug up and turned up the common soil of the Mayor and Burgesses of the town of Nottingham in the holding of John Seliok at Nottingham aforesaid, near Robynhode Well, to the grievous detriment of the said Mayor and Burgesses of the town aforesaid and of the said John Seliok, and against the peace of our said Lord

the King, etc. 9 d., ro. 3.[27]

1548 - Robin Hood's Well (Nottingham)

[1596:]

Richard Sclyocke and his son John grant to Henry Mody, citizen and mercer of London, 2 acres abutting upon 'le Becke' leading from the well (fons) called 'Robyns Wood Well;' [...][28]

1596 - Robin Hood's Well (Nottingham)

[1596:]

Robyn Hood Well alias Saynt Anne Well [...][29]

1597 - Robin Hood's Well (Nottingham)

[1597:]

S. Ann's Well alias Robin Hood's Well [...][30]

1609 - Robin Hood's Well (Nottingham)

[1609:]

One (cot and two) other closes of pasture lying between the said woods and Robbinhoodes Well, in the occupation of Richard Hanton[31]

1625 - Robin Hood's Well (Nottingham)

1625, Good Friday, April 15.

Memorandum, the Companie are allsoe agreed to hould theire meetinge att Robyn Hood well on Monday nexte, accordinge to the antient Custome.[32]

Allusions

1604 - Anonymous - Jack of Dover

THE FOOLE OF HERFORDE

Upon a time (quoth one of the jurie) it was my chaunce to be in the cittie of Herforde, when lodging in an inn I was tolde of a certain silly witted gentleman there dwelling, that wold assuredly beleeve all things that he heard for a truth, to whose house I went upon a sleeveles arrand, and finding occasion to be acquainted with him, I was well entertained, and for three dayes space had my bed and boord in his house, where amongst many other fooleries, I being a traveller made him beleeve that the steeple in Burndwood in Essex sayled in one night as far as Callis in Fraunce, and afterward returned againe to his proper place. Another time I made him beleeve that in the forest of Sherwood in Nottinghamshire were seene five hundred of the king of Spaines gallies, which went to besiedge Robbinhoodes well, and that fourty thousand schollers with elderne squirts performed such a peece of service, as they were all in a manner broken and overthrowne in the forrest. Another time I made him beleeve that Westminster hall, for suspition of treason, was banished [p. 5:] for ten years into Staffordshire. And last of all, I made him beleeve that a tinker should be bayted to death at Canterbury for getting two and twenty children in a yeere: whereupon, to proove me a lyer, he tooke his horse and rode thither; and I, to verrifie him a foole, tooke my horse and rode hither. Well, quoth Jack of Dover, this in my minde was pretty foolerie, but yet the Foole of all Fooles is not heere found that I looke for.[33]

1751 - Deering, Charles - Nottinghamia Vetus et Nova

[p. 73:] Near this Well [...] which is frequented by many Persons as a cold Bath, and reckoned the 2d. coldest in England, there stood anciently a Chappel dedicated to St. Anne, whence the Well obtained the Name it bears, tho' before this Chappel was built, it was known by the Name of Robin Hood's Well, by some called so to this day. The People who keep the Green and Public House to promote a Holy-day Trade, shew an old wickered Chair, which they call Robin Hood's Chair, a Bow, and an old Cap, both these they affirm to have been this famous Robber's Property; [...] this little Artifice takes so well with the People in low-Life, that at Christmas, Easter and Whitsuntide, it procures them a great deal of Business, for at those Times great Numbers of young Men bring their Sweethearts to this Well, and give them a Treat, and the Girls think themselves ill-used, if they have not been saluted by their Lovers in Robin Hood's Chair.

Of the Chappel I find no Account; but that there has been one in this Place is visible, for the East Wall of that quondam Chappel supports the East side of the House, which is built on the Spot where that Place of Worship stood. In the Room of the Altar is now a great Fire-place, over which was found upon a Stone the Date of the building of the Chappel, viz. 1409, which whilst legible one Mr. Ellis a Watchmaker took down into his Pocket-Book, and communicated to me; by this it appears that it was built in the Reign of King Henry IV. 335 Years ago, and who knows whether it might not be founded by that King, who resided about that Time at Nottingham; it did not stand much above 200 Years, for my oft mentioned Anonymous Author does not remember any of the Ruins of the Chappel, who wrote his Account in 1641, which however he might plainly have seen, had he taken Notice of the East Wall of Stone, when all the rest of the present House is a Brick Building.

ST. Anne's Well was about a hundred Years ago, a very famous Place of Resort, concerning which take the above Author's Account in his own words.

AT the Well there is a Dwelling House serving as an Habitation for the Woodward of those Woods, being an Officer of the Mayor. This House is likewise a Victualling House, having adjoining to it fair Summer-Houses, Bowers or Arbours covered by the plashing and interweaving of Oak-Boughs for Shade, in which are Tables of large Oak Planks, and are seated about with Banks of Earth, fleightered and covered with green Sods, like green Carsie Cushions. There is also a Building containing two fair Rooms, an upper and a lower, serving for such as repair thither to retire in Case of Rain or bad Weather. Thither do the Townsmen resort [...] by an ancient Custom beyond Memory.

THIS Well is all Summer long much frequented, and there are but few fair Days between March and October, in which some Company or other of the Town, such as use to Consort [sic] there, use not to fetch a walk to this Well, either to dine or sup, or both, some sending their provision to be dressed, others bespeaking what they will have, and when any of the Town have their Friends come to them, they have given them no welcome, unless they entertain them at this Well. Besides [p. 74:] there are many other Meetings of Gentlemen, both from the Town and the Country, making Choice of this Place rather than the Town for their Rendezvous to recreate themselves at, by Reason of the sweetness and openness of the Air, where besides their Artificial, they have Natural Music without Charge; in the Spring by the Nightingale and in the Autumn by the Wood-Lark, a Bird whose Notes for Variety and sweetness are nothing inferiour to the Nightingale, and much in her Tones, which filled with the Voices of other Birds like inward parts in Song serve to double the melodious Harmony of those sweet warbling Trebles. Here are likewise many Venison Feasts, and such as have not the Hap to feed the Sense of Taste with the Flesh thereof when dead, may yet still fill their Sight with those Creatures living, [...] which all Summer long are picking up Weeds in the Corn-Fields and Closes, and in Winter and hard Weather, gathering Sallets in the Garden of such Houses as lie on the North-side of the Town.

AMONG other Meetings I may not omit one Royal and remarkable Assembly at this Place, whereof myself was an Eye Witness, which was that it pleased our late Sovereign king James, in his Return from Hunting in this Forest, to Honour this Well with his Royal Presence, ushered by that Noble Lord Gilbert Earl of Shrewsbury, and attended by many others of the Nobility, both of the Court and Country, where they drank the Woodward and his Barrels dry."[34]

1790 - Throsby, John - Antiquities of Nottinghamshire (2)

St. ANN's WELL [aka Robin Hood's Well],

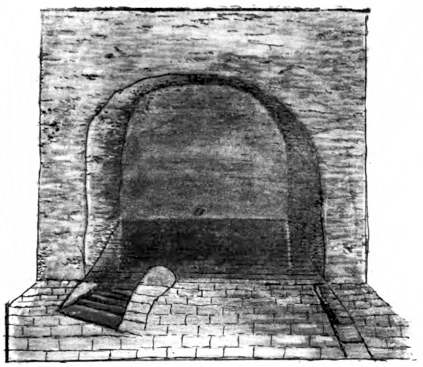

Near Nottingham, was, it is said, a sequestered haunt of the famous Robin Hood, which tradition has given celebrity for ages. It is situate within two miles North East of Nottingham, on the base of a hill, which a century ago, or less, was covered with fine ash trees and copice [sic], as well as a great part of the adjacent fields, which are now cleared of wood, and is [sic] become good land; some portion of which still retains the name of copice [sic] and belongs to the Burgesses of Nottingham. The house which is resorted to in summer time, stands near a Well, both which are shaded by first and other trees. —Here is a large bowling-green, and a little neglected pleasure ground. [p. 171:] The Well is under an arched stone roof, of rude workmanship, the water is very cold, it will kill a toad. [...] It is used by those who are afflicted with rheumatic pains; and indeed, like man other popular springs, for a variety of disorders. At the house were formerly shewn several things said to have belonged to Robin Hood; but they are frittered down to what are now called his cap, or helmet, and a part of his chair. As these have passed current for many years, and perhaps ages, as things once belonging to that renowned robber, I sketched them. They are represented on the annexed plate.

A remarkable circumstance happened here about fifty years since. The story is told thus: A regiment of dragoons lay at Nottingham, at that time, and five of the men agreed to go a deer-stealing, for which purpose they traversed, in the night, over a great extent of country, in vain. Chagrined at the disappointment, in passing over av eminence called Shepherd's-Race [aka Robin Hood's Race], near St. Ann's Well, two of them agreed to go down the hill and steal some geese belonging to the people who lived at St. Ann's Well.A young man who was a servant in the family, and had been out late in company instead of going to bed layed [sic] himself down upon a table in a room, or some other ready and convenient place, where he slept sometime; but was awakened by the noise of the frighted geese, which were disturbed by the soldiers attempting to steal them. The young man being a little elevated in liquor had the temerity to go from the house with an intent to protect his master's or mistress's property, in which attempt he was shot through the head, by a piece placed so near him that his brains were seen scattered about him, were [sic] he fell, in a variety of directions.

The particulars concerning this murder did not come out till about 20 years after the transaction, when two old pensioners, from Chelsea Hospital, were taken up for the fact, and brought to Nottingham gaol; but it turned out that the principals, in the horrid deed, were dead.[35]

1840 - Orange, James - History and Antiquities of Nottingham (1)

There is a famous spring of water near Nottingham, which has for many centuries been constituted a bath, and is said to be the second coldest in England; it was anciently called "Robin Hood's well.'" 1409, Henry IV. built a chapel here, which was dedicated to "St. Anne;" however, it appears to have been regarded in all past ages more as a place of merriment than of Christian worship, and the sylvan bowers by which it was surrounded were more frequently the scene of youthful recreations and impassioned love, than of solemn prayer, that we can hardly think the new name of "St. Anne" being given to this well, was more appropriate than its more ancient one of "Robin Hood's well." Indeed public custom, as well as opinion, seems to have denounced the sacrilege, and to have preferred the old patron rather than the new saint; for the chapel did not exist here quite 200 years, and after its destruction, on the same site there was erected a public house. The east end of that quondam chapel is now the east end of the house, and a large fire-place occupies the room where once the altar stood; and higher in the wall (according to Mr. Ellis, watchmaker, of this town, ninety years ago), there was a stone with a date engraved upon it, 1409.

The people who kept this public-house had an old wicker chair, which was called Robin Hood's chair, a bow, and an iron cap; these reliques were affirmed to have been the property of the famous Robin Hood, and were said to have been the means of drawing multitudes from curiosity to the place, and procured the mayor's woodward, who kept the public-house there, a deal of custom, especially at Christmas, Easter, and Whitsuntide, when husbands and fathers took their spouses and children to enjoy the sports of the seasons; also young men led their sweethearts to mix in the busy throng, and, according to tradition, the fair ones thought themselves slighted by their lovers, if they were not forced to sit down, and then be saluted in Robin Hood's chair.

The following is from an old author quoted by Deering, p. 73:

"At St. Anne's well there is a dwelling-house, serving as an habitation for the woodward of those woods, being an officer of the mayor. This house is likewise a victualling-house, having adjoining to it fair summer-houses, bowers, and arbours, covered by the plashing and interweaving of oak boughs for shades, in which are tables of large oak planks, seated about with banks of earth fleightered, and covered with green sods, like green carsie cushions. There is also a building, containing two fair rooms; an upper and lower one, serving for such as repair thither, to retire in case of rain or bad weather thither do the townsmen resort by an ancient custom beyond memory.

"This well is all summer long much frequented, and there are but few fair days, from March to October, in which some company or other of the town, such as use to consort there, use not to fetch a walk to this well, either to dine or sup, or both, some sending their provision to be dressed; others bespeaking what they will have; and when any people of the town have their friends come to them, they are considered to have given them no welcome, unless they entertain them at this well. Beside, there are many meetings of gentlemen, both from the town and county, making choice of this place, rather than the town, for their rendezvous to recreate themselves at, by reason of the sweetness and openness of the air. Where, besides their artificial, they have the natural music of the woods without charge; in the spring, the nightingale, and in the autumn, the woodlark: a bird whose notes for variety and sweetness, are nothing inferior to the former, which, filled with the voices of other birds, like inward parts in song, serve to double I the melodious harmony of those sweet warbling trebles. Here are, likewise, many venison feasts, and such as feed not the sense of taste, with the flesh thereof when dead, yet may fill their sight with those creatures living, which all summer long are picking up weeds in the corn fields and closes; and in winter, and hard weather, gathering sallads in the gardens of such houses as lie north of the town.

"Among other meetings, I may not omit one royal and remarkable assembly at this place, whereof myself was an eye-witness, which was, that it pleased our late sovereign, king James II., in his return from hunting in this forest, to honour this well with his royal presence, ushered by that noble lord Gilbert, earl of Shrewsbury, and attended by others of the nobility, both of the court and country, when they drank the woodward and his barrels dry."

There is every degree of probability that this was a rendezvous for Robin Hood, and his merry men; its situation (observes the author of "Walks round Nottingham," p. 289), must have been peculiarly adapted for it. Its near approximity to the town, rendered intercourse with it of no great difficulty, and the thickness of the forest in this place, formed a secure barrier against attack; and [p. 370:] when we consider the unquiet times of Richard I. and John, and the strong band which the gallant archer commanded, there can be no great wonder excited at the circumstance of his being able to maintain his ground against every antagonist. Several articles said to have belonged to the outlaw, and which for ages had been exhibited here, were purchased in 1827, by Mr. Raynor, the comedian, and introduced into a melo-drama at one of the London theatres.

In latter days the healing virtues attributed to this spring of water, gave it value in the estimation of the holy mother church, and a building was erected here, called St. Anne's chapel, the priests of which demanded a fee of every one using the water. We visited this place 23rd April, 1839, in company with a friend; it was a lovely morning, and resuscitated nature arising from the langour and death-like faintness of steril winter was assuming her gayest attire, every flower, every leaf, every opening bud of rarer trees, and even the unheeded thorn, sent forth the sweetest aroma, and filled the air with perfume. Arriving at the humble cottage, there were the lofty hills and the lovely valley, but where where the coppice? The well is there, it is a bath, and has a dressing room, both excavated out of the rock; the spring is as strong, and the water as clear as in the days of Henry IV. or bold Robin Hood; but where are the sylvan bowers the umbrageous glens, and all the gay delights and laughing pleasures of woodland scenery? they are gone — and gone for ever.

There is the same cottage called "St. Anne's,'" but it is not the residence of the mayor's woodward now; a widow of the name of Lucy Picard inhabits it, who entertains parties at very moderate charges; there is a very fine large room with board floor, detached from the cottage, in which nearly one hundred people might take tea or dinner. In consequence of sabbath breaking, fights and tumults so often happening, it was found expedient to remove the license in 1825, and there is now nothing intoxicating sold on the premises; there is a delightful garden and pleasure ground, in which the company are allowed to walk, and there are swings for young people to amuse themselves; but the rarest object of attraction is the ingeniously formed maze cut out in the green sward. Hence the party, whether girl or boy, who undertakes to run the Shepherd's Race, must run, or they would fall or tread upon the grassy side, which is to lose the race, and the constant turning and winding about of the path-way awakens the utmost vigilance in the breast of the earnest aspirant of youthful fame. No sight is more pretty or engaging than to behold six or eight [p. 371:] young girls and boys running at the same moment the varying am seemingly interminable windings of the Shepherd's Race.[36]

Quotations

Deering, Charles. Nottinghamia Vetus et Nova (1751):

That by a Custom Time beyond Memory, the Mayor and Aldermen of the Town and their Wives have been used on Monday in Easter Week, Morning Prayers ended, to march from the Town to this Well, having the Town Waits to play before them, and attended by all the Clothing and their Wives, i.e. such as have been Sheriffs, and ever after wear Scarlet Gownes, together with the Officers of the Town, and many other Burgesses and Gentlemen, such as wish well to the Woodward, this Meeting being at first instituted, and since continued for his Benefit.

FORMERLY the Woodward had the House built out of the Ruins of the Chapel allow'd him to live in, who kept a Victualling House there. This Custom is likewise dropt.[37]

Gazetteers

- Dobson, R. B., ed.; Taylor, J., ed. Rymes of Robyn Hood: an Introduction to the English Outlaw (London, 1976), p. 301, s.n. 'Robin Hood's Well, alias St. Anne's Well'.

Sources

- Earp, Joe: St Ann’s Well (Nottingham Hidden History Team)

- Gover, J.E.B.; Mawer, Allen; Stenton, F.M. The Place-Names of Nottinghamshire (English Place-Name Society, vol. XVII) (Cambridge, 1940), pp. 20, 294.

- Stevenson, W.H.; Raine, James, transl.; Baker, W.T., ed.; Guilford, E.L., ed.; Gray, Duncan, ed.; Walker, V.W., ed. Records of the Borough of Nottingham, Being a Series of Extracts from the Archives of the Corporation of Nottingham (London; Nottingham, 1882-1956), vol.

- White, Bob. 'The five unsolved mysteries of Robin Hood' (Nottingham Post, 13 Nov. 2013) (no longer available online).

Discussion

- Greenwood, David. Robin of St. Ann's Well Road (Nottingham, ©2007). Unfortunately this contains many errors, misunderstandings and tendentious interpretations of facts; of interest mainly for its many good illustrations.

- Hope, R.C. 'Holy Wells: their Legends and Superstitions', The Antiquary, vol. XXII (1890), pp. 66-69, see pp. 67-68

- Our Nottinghamshire: Robin Hood's Well: A healing well; by R.B. Parish.

Maps

- 25" O.S. map Nottinghamshire XXXVIII.SE (c. 1882; surveyed 1880-81). NLS has no copy

- 25" O.S. map Nottinghamshire XXXVIII.SE (1900; rev. 1878-83)

- 25" O.S. map Nottinghamshire XXXVIII.SE (1914; rev. 1913)

- 6" O.S. map Nottinghamshire XXXVIII.SE (1885; surveyed 1878-83)

- 6" O.S. map Nottinghamshire XXXVIII.SE (1901; rev. 1899)

- 6" O.S. map Nottinghamshire XXXVIII.SE (1920; rev. 1919)

- 6" O.S. map Nottinghamshire XXXVIII.SE (1947; rev. 1938).

Background

- Art of the Print: Thomas Cooper Moore: St. Anne's Well (Robin Hood's Well)

- Earp, Joe.: Nottingham Hidden History Team: St Ann's Well

- Rotherham: Earl of Shresbury

- Wikipedia: Earl of Shresbury

- Wikipedia: Holy well.

- Wikipedia: St Ann's, Nottingham.

Also see

- St Ann place-name cluster

- Robin Hood's Well (Nottingham) place-name cluster

- Places named Robin Hood's Well

- Robin Hood's Well (Barnsdale)

- Robin Hood's Well (High Park Wood, Moorgreen)

- Robin Hood's Arrows (Chetham's Library).

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Nottingham Hidden History Team: St Ann's Well by Joe Earp.

- ↑ Stevenson, W.H.; Raine, James, transl.; Baker, W.T., ed.; Guilford, E.L., ed.; Gray, Duncan, ed.; Walker, V.W., ed. Records of the Borough of Nottingham, Being a Series of Extracts from the Archives of the Corporation of Nottingham (London; Nottingham, 1882-1956), vol. I, p. 371, item XXX; vol. III, p. 468, s.n. "Brodwell'"; Gover, J.E.B.; Mawer, Allen; Stenton, F.M. The Place-Names of Nottinghamshire (English Place-Name Society, vol. XVII) (Cambridge, 1940), p. 20.

- ↑ Stevenson, W.H.; Raine, James, transl.; Baker, W.T., ed.; Guilford, E.L., ed.; Gray, Duncan, ed.; Walker, V.W., ed. Records of the Borough of Nottingham, Being a Series of Extracts from the Archives of the Corporation of Nottingham (London; Nottingham, 1882-1956), vol. IV, p. 173.

- ↑ Also see Stevenson, W.H.; Raine, James, transl.; Baker, W.T., ed.; Guilford, E.L., ed.; Gray, Duncan, ed.; Walker, V.W., ed. Records of the Borough of Nottingham, Being a Series of Extracts from the Archives of the Corporation of Nottingham (London; Nottingham, 1882-1956), vol. III, p. 475, s.n. 'Robynhode Well'; vol. IV, p. 441, s.n. 'Robyn's Wood Well'.

- ↑ Joe Earp: St Ann's Well (Nottingham Hidden History Team)

- ↑ [OED, well, n. 1. (£).

- ↑ Greenwood, David. Robin of St. Ann's Well Road (Nottingham, ©2007).

- ↑ Stevenson, W.H.; Raine, James, transl.; Baker, W.T., ed.; Guilford, E.L., ed.; Gray, Duncan, ed.; Walker, V.W., ed. Records of the Borough of Nottingham, Being a Series of Extracts from the Archives of the Corporation of Nottingham (London; Nottingham, 1882-1956), vol. I, p. 1.

- ↑ Stevenson, W.H.; Raine, James, transl.; Baker, W.T., ed.; Guilford, E.L., ed.; Gray, Duncan, ed.; Walker, V.W., ed. Records of the Borough of Nottingham, Being a Series of Extracts from the Archives of the Corporation of Nottingham (London; Nottingham, 1882-1956), vol. IV, p. 114 and n. 1.

- ↑ Stevenson, W.H.; Raine, James, transl.; Baker, W.T., ed.; Guilford, E.L., ed.; Gray, Duncan, ed.; Walker, V.W., ed. Records of the Borough of Nottingham, Being a Series of Extracts from the Archives of the Corporation of Nottingham (London; Nottingham, 1882-1956), vol. IV, pp. 117, 133, 163.

- ↑ Stevenson, W.H.; Raine, James, transl.; Baker, W.T., ed.; Guilford, E.L., ed.; Gray, Duncan, ed.; Walker, V.W., ed. Records of the Borough of Nottingham, Being a Series of Extracts from the Archives of the Corporation of Nottingham (London; Nottingham, 1882-1956), vol. IV, p. 173.

- ↑ Stevenson, W.H.; Raine, James, transl.; Baker, W.T., ed.; Guilford, E.L., ed.; Gray, Duncan, ed.; Walker, V.W., ed. Records of the Borough of Nottingham, Being a Series of Extracts from the Archives of the Corporation of Nottingham (London; Nottingham, 1882-1956), vol. IV, p. 256. Stevenson's note numbers silently omitted from the quotation.

- ↑ Stevenson, W.H.; Raine, James, transl.; Baker, W.T., ed.; Guilford, E.L., ed.; Gray, Duncan, ed.; Walker, V.W., ed. Records of the Borough of Nottingham, Being a Series of Extracts from the Archives of the Corporation of Nottingham (London; Nottingham, 1882-1956), vol. IV, p. 291. IRHB's brackets.

- ↑ Stevenson, W.H.; Raine, James, transl.; Baker, W.T., ed.; Guilford, E.L., ed.; Gray, Duncan, ed.; Walker, V.W., ed. Records of the Borough of Nottingham, Being a Series of Extracts from the Archives of the Corporation of Nottingham (London; Nottingham, 1882-1956), vol. IV, pp. 356-57, 359.

- ↑ Stevenson, W.H.; Raine, James, transl.; Baker, W.T., ed.; Guilford, E.L., ed.; Gray, Duncan, ed.; Walker, V.W., ed. Records of the Borough of Nottingham, Being a Series of Extracts from the Archives of the Corporation of Nottingham (London; Nottingham, 1882-1956), vol. IV, p. 358.

- ↑ Stevenson, W.H.; Raine, James, transl.; Baker, W.T., ed.; Guilford, E.L., ed.; Gray, Duncan, ed.; Walker, V.W., ed. Records of the Borough of Nottingham, Being a Series of Extracts from the Archives of the Corporation of Nottingham (London; Nottingham, 1882-1956), vol. IV, p. 373 and n. 7.

- ↑ Stevenson, W.H.; Raine, James, transl.; Baker, W.T., ed.; Guilford, E.L., ed.; Gray, Duncan, ed.; Walker, V.W., ed. Records of the Borough of Nottingham, Being a Series of Extracts from the Archives of the Corporation of Nottingham (London; Nottingham, 1882-1956), vol. IV, pp. 381, 383.

- ↑ In the printed edition that is, for Stevenson et al. by no means printed all records, and they may have omitted some later entries relating to the well.

- ↑ Stevenson, W.H.; Raine, James, transl.; Baker, W.T., ed.; Guilford, E.L., ed.; Gray, Duncan, ed.; Walker, V.W., ed. Records of the Borough of Nottingham, Being a Series of Extracts from the Archives of the Corporation of Nottingham (London; Nottingham, 1882-1956), vol. IV, pp. 385-86.

- ↑ Rotherham: Earl of Shrewsbury.

- ↑ Stevenson, W.H.; Raine, James, transl.; Baker, W.T., ed.; Guilford, E.L., ed.; Gray, Duncan, ed.; Walker, V.W., ed. Records of the Borough of Nottingham, Being a Series of Extracts from the Archives of the Corporation of Nottingham (London; Nottingham, 1882-1956).

- ↑ Deering, Charles. Nottinghamia Vetus et Nova or an Historical Account of the Ancient and Present State of the Town of Nottingham (Nottingham, 1751), sect. I, p. 2.

- ↑ Bob White. 'The five unsolved mysteries of Robin Hood' (Nottingham Post, 13 Nov. 2013; no longer online). See instead: The Wizard of Notts Recommends: Bob White: The five unsolved mysteries of Robin Hood.

- ↑ Bob White. 'The five unsolved mysteries of Robin Hood' (Nottingham Post, 13 Nov. 2013; no longer online). See instead: The Wizard of Notts Recommends: Bob White: The five unsolved mysteries of Robin Hood.

- ↑ Hope, R.C. 'Holy Wells: their Legends and Superstitions', The Antiquary, vol. XXII (1890), pp. 66-69, see pp. 67-68, seems mistakenly to regard the procession to the well as an ongoing tradition.

- ↑ Stevenson, W.H.; Raine, James, transl.; Baker, W.T., ed.; Guilford, E.L., ed.; Gray, Duncan, ed.; Walker, V.W., ed. Records of the Borough of Nottingham, Being a Series of Extracts from the Archives of the Corporation of Nottingham (London; Nottingham, 1882-1956), vol. IV, p. 441, s.n. Saint Ann's Well'.

- ↑ Stevenson, W.H.; Raine, James, transl.; Baker, W.T., ed.; Guilford, E.L., ed.; Gray, Duncan, ed.; Walker, V.W., ed. Records of the Borough of Nottingham, Being a Series of Extracts from the Archives of the Corporation of Nottingham (London; Nottingham, 1882-1956), vol. III, pp. 74, 75.

- ↑ Stevenson, W.H.; Raine, James, transl.; Baker, W.T., ed.; Guilford, E.L., ed.; Gray, Duncan, ed.; Walker, V.W., ed. Records of the Borough of Nottingham, Being a Series of Extracts from the Archives of the Corporation of Nottingham (London; Nottingham, 1882-1956), vol. VI, p. 441, s.n. 'Robyn's Wood Well'. IRHB's brackets. Italics as in printed source.

- ↑ Stevenson, W.H.; Raine, James, transl.; Baker, W.T., ed.; Guilford, E.L., ed.; Gray, Duncan, ed.; Walker, V.W., ed. Records of the Borough of Nottingham, Being a Series of Extracts from the Archives of the Corporation of Nottingham (London; Nottingham, 1882-1956), vol. III, p. 475, s.n. 'Robynhode Well'.

- ↑ Stevenson, W.H.; Raine, James, transl.; Baker, W.T., ed.; Guilford, E.L., ed.; Gray, Duncan, ed.; Walker, V.W., ed. Records of the Borough of Nottingham, Being a Series of Extracts from the Archives of the Corporation of Nottingham (London; Nottingham, 1882-1956), vol. IV, p. 441, s.n. 'Saint ann's Well'. IRHB's ellipsis.

- ↑ Bankes, Richard; Mastoris, Stephanos, ed.; Groves, Sue, ed. Sherwood Forest in 1609: a Crown Survey (Thoroton Society, Record Series, vol. XL) (Nottingham, 1997), p. 67, item No. 584.

- ↑ Stevenson, W.H.; Raine, James, transl.; Baker, W.T., ed.; Guilford, E.L., ed.; Gray, Duncan, ed.; Walker, V.W., ed. Records of the Borough of Nottingham, Being a Series of Extracts from the Archives of the Corporation of Nottingham (London; Nottingham, 1882-1956), vol. V, p. 102.

- ↑ [Wright, T.], ed. Jack of Dover, his Quest of Inquirie, or his Privy Search for the Veriest Foole in England: A Collection of Merry Tales Published at the Beginning of the Sixteenth Century, edited from a copy in the Bodleian Library [by Thomas, Wright], Early English Poetry, Ballads, and Popular Literature of the Middle Ages, edited from Original Manuscripts and scarce publications, vol. VII. London: Printed for the Percy Society by T. Richards, 1842; see pp. 4-5.

- ↑ Deering, Charles. Nottinghamia Vetus et Nova or an Historical Account of the Ancient and Present State of the Town of Nottingham (Nottingham, 1751), pp. 72-74.

- ↑ Thoroton, Robert. The Antiquities of Nottinghamshire: Extracted out of Records, Original Evidences, Leiger-books, Other Manuscripts, and Authentic Authorities. Beautified with Maps, Prospects, and Portraitures. 2nd ed. (Nottingham, 1790), vol. II, pp. 170-71.

- ↑ Orange, James. History and Antiquities of Nottingham, in which are Exhibited the Various Institutions, Manners, Customs, Arts, and Manufactures of the People; their Social and Domestic Habits; Civil and Political Conditions, under Every Successive Government, from their Conquests by the Normans, Danes, Saxons, Romans, and Early British Dependency, down to the Present Time: Forming a Condensed but Comprehensive English as well as Local History, Chronologically Arranged (London; Nottingham, 1840), vol. I, pp. 368-

- ↑ Deering, Charles. Nottinghamia Vetus et Nova or an Historical Account of the Ancient and Present State of the Town of Nottingham (Nottingham, 1751), p. 125. IRHB's brackets. Italics and capitals as in Deering. I have changed the way in which quotation of Deering's MS is indicated in the text.

Image gallery

Click any image to display it in the lightbox, where you can navigate between images by clicking in the right or left side of the current image.

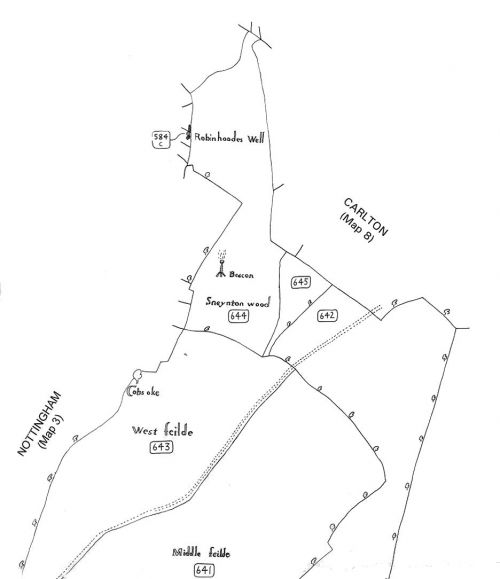

Detail of the Sneinton portion of Peter Burgess's retracing of Richard Bankes's (c. ?1609) MS map (PRO MR 1142 pt. 1) / Bankes, Richard; Mastoris, Stephanos, ed.; Groves, Sue, ed. Sherwood Forest in 1609: a Crown Survey (Thoroton Society, Record Series, vol. XL) (Nottingham, 1997), Map 5: Sneinton.

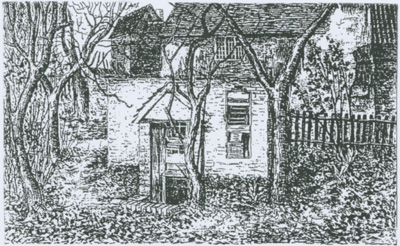

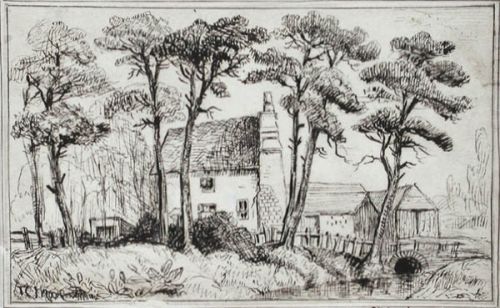

'‘Robin Hood’s Well' (i.e. gamekeeper's house) by Thomas Cooper Moore, 1856 / Art of the Print.

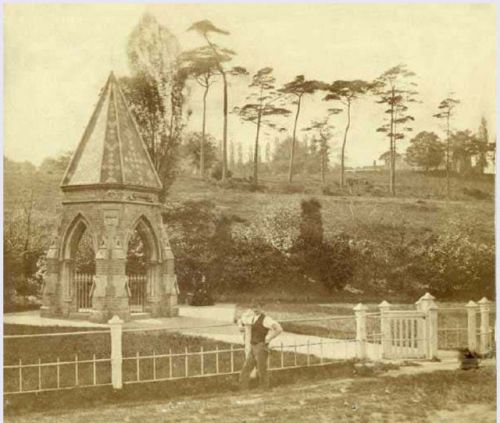

Robin Hood’s Well, c. 1867–73 / The Paul Nix Collection, via Nottingham Hidden History Team; used by permission.

The immersion bath at the holy well / Thoroton, Robert. The Antiquities of Nottinghamshire: Extracted out of Records, Original Evidences, Leiger-books, Other Manuscripts, and Authentic Authorities. Beautified with Maps, Prospects, and Portraitures. 2nd ed. (Nottingham, 1790), vol. I, plate inter pp. 170-71.

What was left of Robin Hood's Chair c. 1790 / Thoroton, Robert. The Antiquities of Nottinghamshire: Extracted out of Records, Original Evidences, Leiger-books, Other Manuscripts, and Authentic Authorities. Beautified with Maps, Prospects, and Portraitures. 2nd ed. (Nottingham, 1790), vol. I, plate inter pp. 170-71.

Another priceless relic: Robin Hood's Helmet as it looked c. 1790 / Thoroton, Robert. The Antiquities of Nottinghamshire: Extracted out of Records, Original Evidences, Leiger-books, Other Manuscripts, and Authentic Authorities. Beautified with Maps, Prospects, and Portraitures. 2nd ed. (Nottingham, 1790), vol. I, plate inter pp. 170-71.